I occasionally have a free hour in my schedule and I

visit the Cape Hatteras National Seashore library to vacuum it for interesting

stories. This is considered to be my research time. I recently came upon an

outstanding book called Diving the

Graveyard of the Atlantic by Roderick M. Farb. It’s full of great yarns

about the sinking of ships.

The Outer Banks of North Carolina holds the bones of

thousands of ships, hence the superior lighthouses that act as a pearl necklace

long the coast. What I didn’t realize, however, is the story of German U-boats

that ranged along this coast in 1942. While I was an infant of three or four, I

remember my dad’s task during the war of being an Air Raid Precaution officer

in Inverness, Scotland. His job required him to walk the streets of our

neighborhood at night to check there were no chinks of light escaping from the

houses. And he, being a stickler for detail, would bang on the door if he found

someone who had sloppily left a blanket askew on a window.

But over here, along the Atlantic seaboard,

Americans initially were oblivious to this need to block out the light and, it

turns out German U-boats took full advantage of this “it can’t happen to us”

attitude. They formed wolf packs of subs off the Outer Banks and in the first

three months of the war, U-boats attacked and sank 70 U.S. tankers, freighters

and other assorted ships. Astonishingly, the U.S. Navy was so ill-prepared for

these attacks that it took the U.S. three months to get its act together, snub

out the shore lights, the navigation buoys and, yes, even the lighthouses.

In Diving the Graveyard of the Atlantic, Farb tells the story of U-boat 352 and the U.S. Coast Guard cutter

Icarus. When they met, no help came to either of them. The battle was a fight

to the finish. Today the loser sits on a sandy bottom, 115 feet deep, 20 miles

off Morehead City, North Carolina.

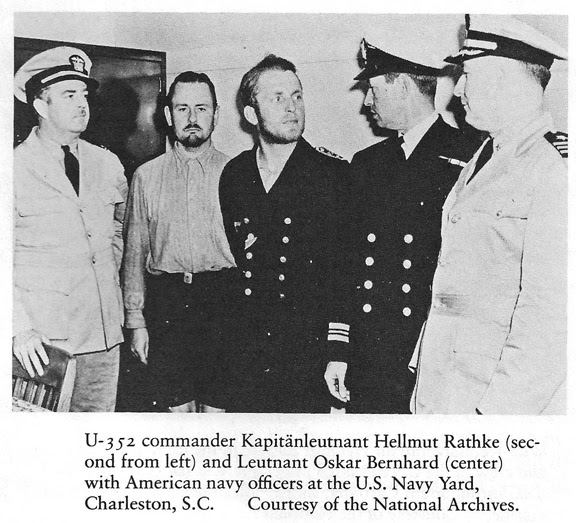

U-boat 352, captained by Kapitanleutenant Hellmut

Rathke edged out of St. Nazaire harbor in France on the morning of April 4,

1942. An East Prussian by birth, Rathke was 32 years old and considered a

rising star in the U-boat arm of the German navy.

Meanwhile, up in Staten Island, N.Y., the U.S. Coast

Guard cutter Icarus, commanded by Lt. Maurice D. Jester, received orders to

proceed south to Key West, Florida. As

it cleared the harbor in New York, a passing tug signaled G-O-O-D-L-U-C-K.

Icarus signalman flashed back T-H-A-N-K-S-W-E-W-I-L-L-D-O-O-K.

They were destined to meet off the Outer Banks on

May 9. Rathke had spent many hours training his raw crew on crash dives and

other maneuvers as they slowly crossed the Atlantic. He allowed his crew time

to sunbathe on the deck of the sub but he also ran drills to get them in shape

on their first expedition to the coast of North America.

When Rathke arrived offshore, he would sit his

U-boat on the bottom during the day and then he’d bring the sub to the surface

in the dark. He’d allow the radioman to tune in U.S, radio stations that were

transmitting jazz music for the entertainment of the crew. He tried several

times to take out ships but his torpedoes went wide. He was bombed by a

vigilant plane but managed to escape damage.

Finally, late on May 9, he watched a single mast

rise above the horizon. Rathke ordered a crash dive and maneuvered toward the

sighting. He ordered one and two torpedoes flooded. They were loaded with

electric torpedoes of the latest design. He fired in quick succession. Lt.

Ernst, the U-boat’s No. 2 officer, adjusted the submarine’s trim but the adjustment

was too severe and Rathke lost sight of his target.

Suddenly the U-boat shook from the recoil of a

distant explosion. Rathke ordered the U-boat brought up to periscope depth so

he could observe the target. He believed it was a small freighter. It was,

however, the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Icarus.

What he didn’t know was that his torpedoes had actually ploughed

into the sand close to Icarus and had exploded. Icarus was jarred but was fully

operational. She swung around and headed directly for the sound pattern the

radioman had identified as U-352.

The submarine crew cringed as Icarus came

overhead. The first depth charge exploded next to U-352’s deck gun. Another

went off beside the engine room. Two charges drifted down alongside the conning

tower. Icarus trembled under the impact as these depth charges exploded.

Aboard U-352, every gauge exploded and shards of

glass flew everywhere. Lt. Ernst was flung into the control panel, crushing his

skull. Lights flickered throughout the U-boat and then died.

Both electric motors aboard the sub were wrenched

from their mountings and the boat was without power. One motor could run

intermittently.

Rathke analyzed his situation. His No. 2 officer was

dead. He was limping, without instruments and only a small amount of power in

one engine. But he refused to give up the ship. What he didn’t know was that a

large amount of sheet metal on the bridge had been blown away and the buoyancy

of his vessel was questionable.

The radiomen aboard Icarus tracked the sub and knew

he was trying to slip away but Lt. Jester brought Icarus around for a second

attack. U-352 was about to be a dead

boat.

Rathke ordered silence and every man stood

absolutely still. The only sound was a drip from the No. 1 torpedo tube. When

it became a spurt of water, one of the torpedomen cried out. Rathke sent a man

forward to demand silence.

No depth charges had fallen in 15 minutes. The

Icarus’ engines died away and then returned, ominously strong.

The new round of depth charges knocked U-352 on her

side and she settled on the bottom, one of her buoyancy tanks was ruptured.

The first man out of the sub had his right leg blown

off by a machine-gunner aboard Icarus. The three-inch gun aboard Icarus was

punching out as long and hard as it could go.

As the Germans escaped from their sunken sub, Rathke

spotted his machinist who had his leg blown away. He was in a sea of blood. The

captain removed his belt and tried to staunch the flow of blood from the

severed leg while the hail of gunfire continued around him.

Rathke called for his men to have courage as the

hail of bullets continued from Icarus. Helplessly, he watched them being shot

to death in the water. Rathke shouted for mercy and for help and his men joined

him.

John Bruce, aboard Icarus remembered seeing the men

in the water. He screamed, “For God’s sake, don’t shoot them in the water.” But

he was derided by his fellow crewmen. One of the men said, “That could have

been us.”

The gunners on the stern stopped but the gunners on

the bow maintained their firing. Three minutes after U-352 went down, a runner

from the bridge went to each gun and ordered a ceasefire.

After one more round of dropping depth charges on

the sunken U-boat, the Icarus headed away from the scene. Lt. Jester was unsure

of his authority and didn’t know if he had to do anything other than sink

submarines.

He sent a message to Norfolk, stating he had 30-40

men in the water and asked if he should pick them up. There was no reply.’

Next he tried Charleston and still there was no

reply. The message was received and acknowledged.

After 10 minutes, the radioman asked if Charleston

had any message for Icarus. The answer came back: “No.”

The radioman saw that Icarus was pulling farther and

farther away from the U-boat and he went up the chain of command asking again

if Icarus should pick up survivors. After 40 minutes, he asked again. This time,

he received a coded message authorizing the pickup of the U-boat crew along

with orders to take them into Charleston.

Rathke saw Icarus returning and he gathered his crew

around him. He told them: “Remember your duty. Do not tell the enemy anything.”

Rathke asked that his wounded men be taken aboard

first. Rathke was the last man out of the water. Fourteen of his crewmen died

in the engagement. It was the first U-boat to be sunk by the U.S. in World War

II by the U.S. Coast Guard.

No comments:

Post a Comment